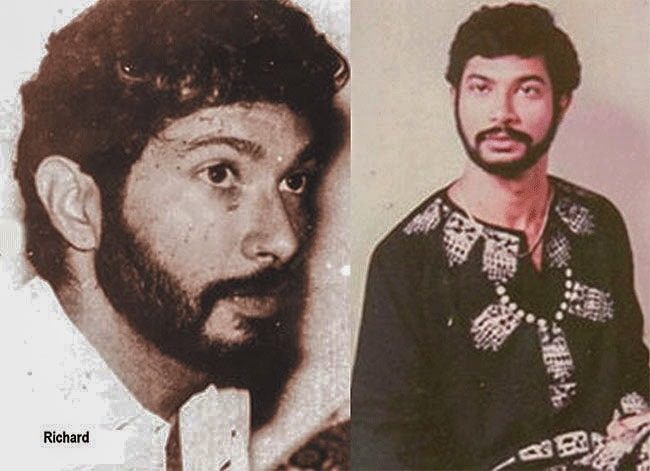

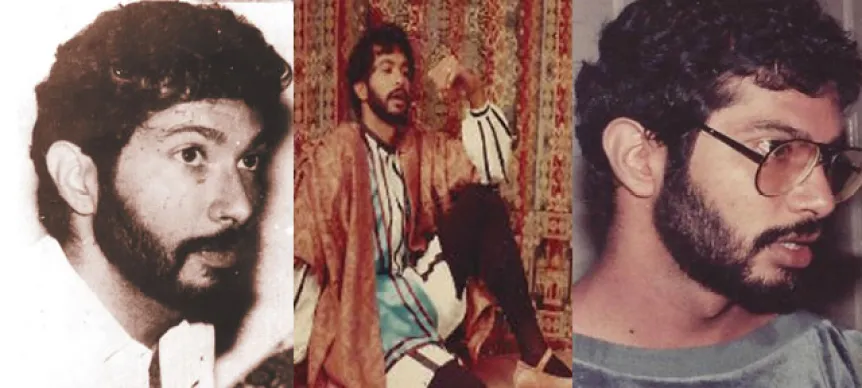

February 18, 2025, marks the 35th year of the abduction and brutal killing of journalist, teacher, poet, playwright, actor and activist Richard de Zoysa.

Richard de Zoysa’s bullet-drilled body, found washed up on Moratuwa beach on 18 February 1990, brought the entire nation to a standstill. A victim of State-sanctioned terror, his death, for many, marked the tragic end of a once fearless voice against tyranny descending into madness. Ironically, his demise amplified his influence, exposing the brutal reality of State terror in Sri Lanka. Today, 35 years after his death, we explore why Richard’s death had such a profound impact, and how it inspired a new generation of resistance to carry forward his legacy – why, even in death, Richard was more powerful than ever.

State terror did not begin with Richard de Zoysa’s assassination. From the 1970s until Richard’s death in 1990, numerous figures such as lawyers like Wijedasa Liyanarachchi, student movement leaders like Padmasiri Thirimavitharana and Nimal Balasuriya, over 60,000 JVP activists including its leader Rohana Wijeweera, along with countless other extrajudicial killings, assaults, threats, intimidation, and enforced disappearances, were either directly or indirectly linked to the regimes of JR and Premadasa. However, the assassination of Richard de Zoysa emerged as the defining tragedy of the decade for several reasons.

One key reason was his vibrant and multifaceted personality–as a journalist, news anchor, actor, human rights activist, playwright, and dramatist–coupled with his masterful use of language, predominantly English. Further, his involvement with Inter Press Service grabbed the international spotlight to this incident making him a martyr.

Conversely, his background and influence carried equal weight in amplifying Richard’s voice following his death. Before this, most of those who were killed or forcibly disappeared–whom Richard also stood for–came from rural, lower-middle-class, or working-class backgrounds, their voices fading without the momentum to reach wider attention. Hence, to the Colombo middle class, which had little to no exposure to – and therefore hardly any concern about – State terror, Richard’s assassination sent a shock wave. The message was clear: The gun was now pointed at them too. As a result, the socio-political outcry that followed, echoed across all channels, exposing the corruption and brutality of many institutions of the Government with greater force, preventing his death from becoming just another statistic of the era.

Justice delayed and denied

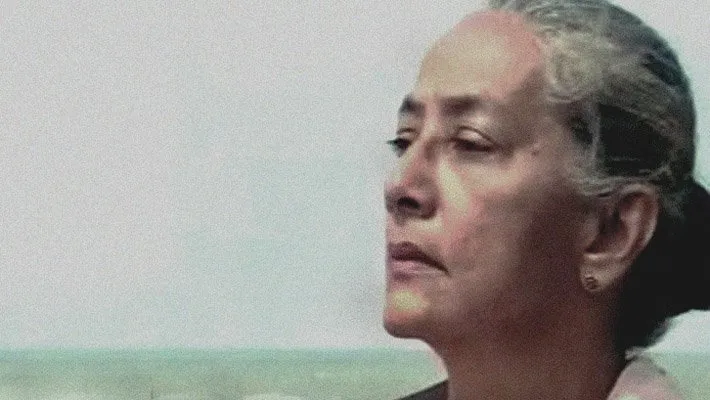

Impartiality, credibility, due diligence, and the fundamental duty of the Police and the Attorney General’s Department (AG) in seeking justice came under open scrutiny following Richard’s death. From the failure of the Police (the Superintendent or Assistant Superintendent of Police) to report this crime to the AG – as required by Section 393(5) of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CCP) – a chain of failures in Richard’s murder investigation were uncovered, revealing the Police’s inefficiency and lack of interest in delivering justice. The Police failed to request an identification parade immediately, following Richard’s mother, Dr. Saravanamuttu’s identification of then SSP Ronnie Gunasinghe as one of Richard’s abductors. Essential documents, including the investigation report and a summary of witness statements, were not submitted during the magisterial inquiry, despite the magistrate’s repeated requests. In every way, the Police signalled to the victim’s mother and the thousands of Sri Lankans closely following the trial, that justice was out of reach – and that they had no intention of pursuing it.

The other most-despicable revelation was the role AG played in this incident. The involvement of the AG – which was expected as soon as Richard’s body was found – was delayed until 11 June, 1990, despite the fact that Section 393 of the CCP allowed the AG to intervene earlier, given the widespread publicity and a formal complaint from Richard’s mother, Dr. Manorani Saravanamuttu, on 28 March,1990.

Even more troubling was the AG’s response to SSP Ronnie Gunasinghe’s involvement. When this was reported to the court, the AG chose to request that the evidence – originally set to be presented under Section 138 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CCP), which permits the magistrate to publicly examine the evidence, assess its merits, and decide whether to charge Gunasinghe – be submitted, instead, under Section 124. This change effectively reduced the magistrate’s role to a mere assistant in the investigation, stripping him/her of the authority to make meaningful legal determinations.

These instances, however, did not go unnoticed by national and international critics. They were strongly condemned in the Magisterial Inquiry into the Homicide of Richard de Zoysa by Anthony Heaton-Armstrong of the International Commission of Jurists, the Statement on the Murder of Richard de Zoysa by Chanaka Amaratunga and Rajiva Wijesinha, and, most notably, The Attorney General’s Role in the Extra-Judicial Execution of Richard de Zoysa by Batty Weerakoon, the attorney who represented Richard’s mother. All accounts consistently indicate that the investigation was conducted under the fixed assumption that SSP Gunasinghe could not have been involved, marked by intentional delays and negligence.

Furthermore, it is important to note that both the investigation and court proceedings took place in a climate of intimidation. The victim’s mother, Dr. Saravanamuttu, and her attorney, Batty Weerakoon, were repeatedly threatened through letters and phone calls, warning them not to appear in court or continue with their submissions. After numerous complaints to the authorities, two police officers were assigned for their protection – yet they too became targets of similar threats.

These incidents raise pressing questions: were the Police and the Attorney General’s Department genuinely seeking justice, or were they shielding the perpetrators by delaying and obstructing legal proceedings? What happened to the right to a fair trial? An even more unsettling realisation emerges – this case only garnered attention because it involved a high-profile murder. But what about the over 60,000 other killings? Were they all subjected to the same corrupt and compromised legal process? Did the families and close friends of the victims ever have the chance to exercise their right to justice?

Though the Government of the time chose to ignore these questions, Richard – lying among the dead – pulled back the curtain, revealing the truth to the world; the grave human rights violations, the systemic injustices, and the stark reality that, if not for his death, the full extent of these crimes might have remained hidden forever.

The Richardian memory in literature

Richard’s socio-political critique was even more subtle and engaging in his literary work. His social class and education provided him with access to Sri Lanka’s aristocracy, making his poetic attacks more close quarter. The most intriguing factor is that Richard’s best poetry comes in his 20s, standing alongside the finest of Sri Lankan English poets like Lakdasa Wikkramasinha, Jean Arasanayagam, and Anne Ranasinghe. Following his death, his work reached a wider audience, studied, reviewed, and critiqued for the poetic depth and power embedded in them.

The defining strength – and indeed the very essence – of Richard de Zoysa’s poetic voice lies in his masterful use of symbolism and allegory, which vividly resonated with the socio-political realities of Sri Lanka. In Gajagavannama, he draws inspiration from a real-life incident of a rampage during the 1983 Navam Perahera in Colombo, transforming it into a powerful metaphor. The elephant, both a literal force of destruction and the emblem of the ruling United National Party (UNP) under J.R. Jayewardene, becomes an allegorical representation of the regime’s brutal crackdown on Tamil communities in the early 1980s – a poetic rendering of State-sponsored violence.

Broken Promise (1981) is another of Richard de Zoysa’s sharp critiques of the Jayewardene Government’s failed pledges. It satirises the contradictions of a regime that promised economic, social, political, and press freedoms but instead suppressed dissent and manipulated public perception. Richard’s words foreshadowed the increasing State violence of the 1980s, making Broken Promise a powerful act of political defiance. Many of his other poems, such as Animal Crackers and Rites of Passage, cut to the core of the political hypocrisy, corruption, duplicity, and vanity that defined his time. What he might have achieved had he lived beyond 18 February, 1990, is open to speculation, but it would surely have been nothing short of a blistering legacy.

Richard de Zoysa’s poetry and murder sparked decades of literary, legal, and cinematic reckoning. In 1990, This Other Eden: The Collected Poems of Richard de Zoysa – published by the English Association of Sri Lanka – ensured his politically charged verses would never be erased. A decade later, in 2000, Rajiva Wijesinha’s Richard de Zoysa: His Life, Some Work, A Death brought together his poetry and critical essays, cementing his place in Sri Lankan letters.

The legal quest followed. Batty Weerakoon’s The Attorney General’s Role in the Extra-Judicial Execution of Richard de Zoysa (1991) pulled apart the State’s role in his murder, while the International Commission of Jurists laid it all bare in the Magisterial Inquiry into the Homicide of Richard de Zoysa. Chanaka Amaratunga and Rajiva Wijesinha, in their Statement on the Murder of Richard de Zoysa, traced the cover-up in meticulous detail.

The next generation carried his name forward. The Pen of Granite: A Memorial Edition (2015), compiled by Dhanuka Bandara, Manikya Kodithuwakku, and Vihanga Perera, alongside Prabhath Chinthaka Meegodage’s Richard de Zoysa: Nihanda Kala Handa (2020), ensured the story remained alive.

Efforts to suppress his legacy only made it stronger. The Defence Ministry’s refusal to permit Nilendra Deshapriya’s They Dance Alone, citing the ‘inappropriateness’ of revisiting the past, exemplified the State’s ongoing discomfort with his story. Yet, artistic engagement with Richard’s life and work continued to expand. In 2022, The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida won the Booker Prize, with its protagonist, Maali, being loosely inspired by Richard de Zoysa – a testament to his enduring impact on literature and political discourse. In 2025, Ashoka Handagama’s Rani brings to the screen the relentless pursuit of justice led by his mother, Dr. Saravanamuttu. Far from being forgotten, Richard’s poetry and tragic death remain central to discussions on State violence, media freedom, and artistic resistance in Sri Lanka.

A legacy that refuses to die

Richard de Zoysa – along with thousands of others – was subjected to torture, extrajudicial execution, or enforced disappearance in a country where the Constitution ostensibly guarantees freedom of speech, expression, and publication (Article 14(1)(a)), while also prohibiting torture and cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment (Article 11). These constitutional assurances, however, have repeatedly been undermined by State-sanctioned violence and impunity. Richard de Zoysa’s fate in 1990 was neither the first nor the last. His legacy of fearless journalism has been carried forward by many, often at great personal cost.

The killings continued. Journalist Aiyathurai A. Nadesan was murdered in 2004. Dharmarathnam Sivaram, a senior editor of TamilNet, – and a close friend of Richard De Zoysa – was abducted and killed in 2005. The journalist and broadcaster Sampath Lakmal de Silva was assassinated in 2006. Lasantha Wickrematunge, editor of The ‘Sunday Leader’, was murdered in broad daylight in 2009 – his death, much like Richard’s, sparked both national and international outrage. However, the pattern remained unchanged. Cartoonist and political analyst Prageeth Ekneligoda disappeared on 24 January, 2010, and his fate remains unknown to this day.

Attacks and abductions ensured fear remained a constant. For many, exile was the only escape. Associate editor of ‘The Nation’, Keith Noyahr, fled the country after being abducted and brutally beaten for hours in 2008. Former editor of ‘Divaina’ and founding editor of ‘Rivira’, Upali Tennakoon, was assaulted in 2009 by men on motorcycles armed with knives and sticks. He and his wife, Dhammika, narrowly survived and later went into exile. Sunday Leader editor Frederica Jansz left the country after repeated death threats. Poddala Jayantha, the secretary of the Sri Lanka Working Journalists Association, was brutally attacked in 2009 and later fled.

These names represent only a fraction of those who have paid the price for dissent. Their voices, like Richard’s, refused to be silenced. The cycle of suppression persists, yet the pursuit of truth remains relentless. The legacy of media freedom in Sri Lanka is not dead–only carried forward by new voices willing to risk everything to speak.

The struggle for truth persists, despite threats and exile. As Bertolt Brecht wrote, “Yes, there will be singing. About the dark times.” Richard’s story is not just about the past–it is a warning, a legacy, and a relentless demand for justice that refuses to fade, that is constantly reborn. The fight he took part in is far from over.

Source: ceylontoday.lk