With limited private sector jobs, young Indians from modest backgrounds see government jobs as crucial for social mobility. However, these positions are scarce and expensive to pursue, often requiring up to ten years of exam preparation.

Rajesh Kumar often paces in his small room in Prayagraj, in India’s northern Uttar Pradesh state, wondering if he will ever pass the history teacher civil service exam. Occasionally, a phone call from his parents about someone from his village successfully passing a civil service exam provides some perspective. “When that happens, I think about those who have been preparing for ten or 15 years,” says the 29-year-old. He has only been at it for six years.

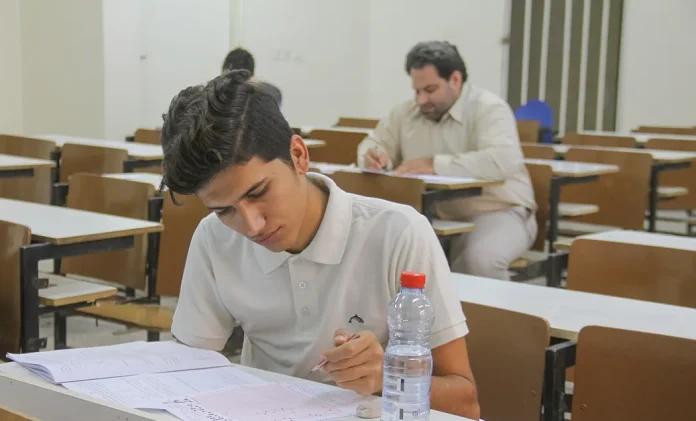

While the lengthy preparation time may seem astonishing, it has become the norm for thousands of students in Prayagraj (formerly Allahabad), a city of one million and home to dozens of civil service exam prep centers. This situation is a consequence of an economy that, despite robust growth, fails to generate sufficient jobs for the millions of youths entering the workforce each year.

With rising unemployment and underemployment, prestigious and stable civil servant jobs are even more sought after than ever before, even if it means spending 5-10 years preparing for exams and selection rates often under 1%.

As a farmer’s son, Rajesh pays 20,000 rupees (about $224) annually for his room with money sent from his parents, sparing him the need to juggle studies with a side job.

Unlike Rajesh, his neighbor, Suraj Kumar, 25, alternates his study sessions with trips to his native village to farm wheat and sugarcane on his family’s small plot. He has been trying to pass the exams for two years to join the police or become a forest ranger. “I picked these exams randomly because the tests are similar and they play to my strengths,” said Suraj, sitting upright in his neatly arranged room. Lacking a computer, he connects a keyboard to his phone with a cable and types out his essays on a 15 cm by 8 cm screen.

“It’s a profitable business”

In Prayagraj, private coaching centers for public sector exams are numerous. Advertisements dominate the streets, promoting top “coaches” and proudly displaying the faces and names of former students who have become civil servants. “The government makes big announcements, but in reality, there aren’t enough opportunities in the private sector,” explained Saurabh Sheklar, manager of Ananya Coaching, a prep school specializing in teaching exams. “Most of our students are farmers’ children. For them, a public job remains the best way to climb the social ladder, for a limited investment.”

Behind him, a math lesson streams on YouTube. The institute has seven classrooms and a studio for recording lessons for remote students. “It’s a profitable business,” acknowledged Anand Shukla, the head of the institution. “Young people in Uttar Pradesh only dream of public jobs. They don’t care about the private sector; there’s no future in it.” This perception was further reinforced by the traumatic experience of the COVID-19 pandemic, during which millions of Indians lost their jobs in the private sector. From a rural perspective, only a “government job” seemingly offers a stable future.

For many women, the pressure is even greater. Neha Patel, 26, paid 14,000 rupees annually for several years before switching to a new institution offering an introductory rate of just 1,000 rupees a year, a sign of the sector’s competitiveness. For her, the exams represent more than just a chance for social advancement. “In the village, they think a woman is only good for cooking and having children,” she said outside a city library. “If you want to emancipate yourself, becoming a civil servant is the only way out.”

“The pressure, for women, is marriage”

After seven years of preparing for administrative exams in the region, Neha has yet to succeed. However, she knows the curriculum so well that she now gives private lessons and runs a YouTube channel for exam preparation with 7,000 subscribers. Among her friends and the students she coaches, nearly all face the additional pressure of potentially having to return to their villages to marry in case of failure. “I get a lot of calls from students in tears, whose parents have told them it’s their last year of prep,” she shared. “The pressure, for women, is marriage.” She escaped this pressure thanks to her siblings. As former prep students who have all passed their exams, they now help to cover the cost of their youngest sister’s studies.

In contrast, Vrihaspati Mani Tripathi is struggling financially. Since 2020, the 27-year-old has been unable to afford prep classes and has been studying for the public service exams on his own. To pay for his lodging, he borrows money from his elder brother and returns to work in his village as a seasonal laborer every three to four months. Despite the challenges, he remains confident in his chances of soon landing his dream job. “I give myself another year, a year and a half to make it,” he said with a relaxed smile. However, his leg begins to tremble when asked about the selection rate for the administrative exam he hopes for. During the February session, the 220 available positions attracted 574,538 candidates.