[ad_1]

This podcast from Teacher

is supported by MacKillop Seasons, whose Seasons for Life project supports schools with loss and grief following a suicide and other loss event.

Hello and thanks for downloading this podcast from Teacher, I’m Jo Earp.

The PISA 2022 international results have just been announced. The Programme for International Student Assessment, to give it its full title, measures the knowledge and skills of 15-year-old students in reading, mathematical, and scientific literacy. Rather than how well they’ve learned a particular piece of content or part of the curriculum, it assesses their ability to apply their knowledge and skills to real-life problems and situations. Singapore once again topped the tables across the board, with its students performing significantly higher than their international counterparts across all 3 domains.

PISA 2022, which was delayed by a year because of the pandemic, involved nearly 700,000 students from 81 OECD member and partner economies. Here in Australia, 13,347 students from 743 schools participated. Each cycle of PISA has a nominated major domain – the latest one being mathematics. In this special episode I’m joined by Professor Geoff Masters, CEO of the Australian Council for Educational Research, to talk about Australia’s performance, what we could learn from top performer Singapore, and some of the education reforms taking place in other parts of the world. At the beginning of our chat, we talk about a graph showing proportions of high and low performers in Australia and Singapore in mathematical literacy – if you want to have that ready to look at, you can find it in the podcast transcript at teachermagazine.com. I hope you enjoy the episode.

Jo Earp: Professor Geoff Masters, thanks for joining us again at Teacher, it’s always great to have you here.

Geoff Masters: It’s a pleasure.

JE: So, the results of the latest PISA assessment have just been released. As usual, there’s a lot there for Australia to digest. What can we learn from these latest PISA results?

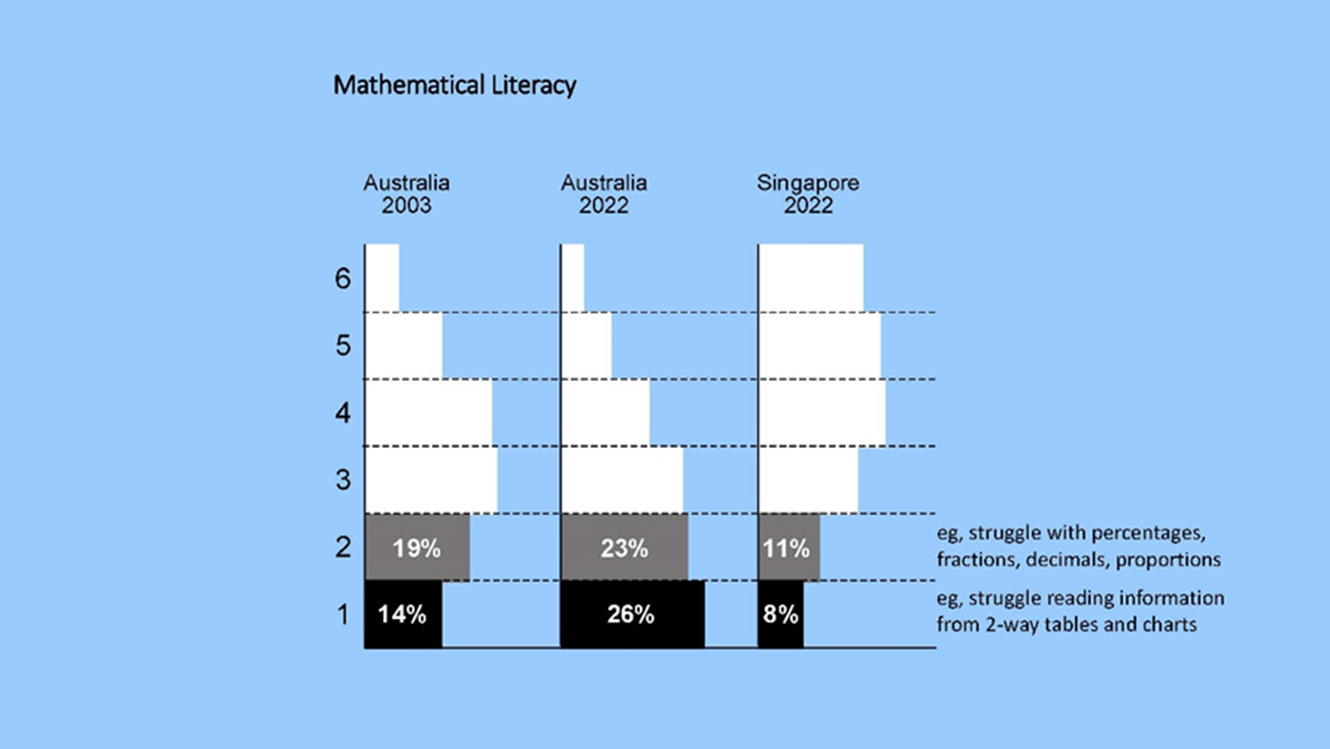

GM: Well, I think there’s both good news and bad news. The good news is that after a long-term decline in Australia’s performance at 15 years of age in reading, mathematical and scientific literacy, over the last couple of cycles we seem to have levelled out. So, we haven’t seen a continuation of the decline that had occurred over the previous couple of decades. So that’s good news. At the same time, a number of other countries did see declines. So, what that means is that while in an absolute sense Australia’s performance remained the same as it had been back in 2018, our standing in relation to other countries actually improved; they went down, we stayed where we were. So that’s a piece of good news. The bad news, I think, is that there’s still a very large proportion of Australian 15-year-olds who are performing at worryingly low levels, and you can see that in this graph.

The main assessment domain in 2022 was mathematical literacy. So, this graph shows results in mathematical literacy. And what you can see in the lowest levels – levels 1 and 2 – is that about half, about 49% of Australian 15-year-olds, are performing at those 2 lowest levels. Now, Level 3 is what’s called the National Proficient Standard –it’s the level that we expect 15-year-olds to reach in their mathematical literacy. So, about half of all Australian students, according to this PISA survey, are performing below the level that we’ve set as our national minimum standard for PISA, and more than that, you can see that 26% of students are performing at the very lowest level, level 1.

Just to give you an idea of what that means, you can see over on the right that students in level 2 typically would struggle with things like applying multiple calculations to solve a problem, dealing with fractions, percentages, decimals, proportional reasoning, the sorts of things that most students would be expected to learn to some extent in primary schools. And then at the lowest level, level 1, these are students who really are likely to struggle in applying mathematics to everyday kinds of situations beyond school. So, things like reading information from a 2-way table, reading information from charts and from graphs. So, you can see, this graph shows that there’s been a decline since 2003 in Australia’s results – more students now are performing at these very low levels 1 and 2. And the graph also shows the highest performing country in the world, Singapore, and the relatively low percentage of students performing at these low levels in Singapore.

JE: So, there are worrying signs there, as you say, and the graph shows that perfectly. And if you’re listening just to this audio on the Teacher podcast, I’ll pop a chart into the full transcript of this, which is at teachermagazine.com. This isn’t just an isolated result though, is it? It’s not just PISA that’s been sounding the alarm bell, basically?

GM: No, we’ve seen similar things through other assessment programmes, for example, NAPLAN has shown us that there’s been no improvement in numeracy levels at any of the year levels (3, 5, 7 and 9) over a period from 2008 to 2022. So there’s been no improvement there. NAPLAN’s a little different from PISA. NAPLAN assesses basic numeracy skills and literacy skills, of course. PISA is a little different in that it is looking at students’ abilities to use their reasoning skills and their understandings of mathematics to solve everyday kinds of problems. So, they’re a little different as assessment programmes, they look at different things. But it is certainly the case that NAPLAN also shows that there has been no improvement in numeracy levels over the last 14 years.

JE: Before we talk about the top performers, then, I just want to briefly mention the pandemic. Obviously, there were a lot of lockdowns here, particularly in Australia and in Victoria, that shift to remote teaching. How much of an impact will that have had on the results? Will we kind of look back and think, ‘oh, there’s a little asterisk against these ones’.

GM: Yeah, it’s an interesting question. It’s a little hard to know, I think. The PISA assessment that was planned for 2021, was delayed until 2022 because of the pandemic. So, the period we’re looking at really is a 4-year period now – 2018 to 2022. As I said, what one can see in many countries is that there has been a decline over that period and I’m sure that many of those countries will be quick to say that’s the impact of the pandemic, and it may well be. As I said, in Australia, we can’t see the same kind of decline that many other countries have seen.

So, it’s difficult to know. What we can see is, even in states like Victoria where there were quite significant lockdowns, there’s not a lot of evidence that that had a different kind of impact on student results. So, there’s not a bigger decline in performance in Victoria. In New South Wales, science literacy results actually went up between 2018 and 2022, so it’s an interesting question you’re asking. I think there will be a lot of interest in Australia and internationally in the 2025 results, where we’ll be able to look in a longer time frame at the potential impact that the pandemic had on student learning.

JE: Yeah, so time will tell basically on that one. Let’s have a chat about the international performers then. As in previous PISA test cycles, Singapore again leads the way – significantly outperforming all the other countries, not just in maths, but in reading and science as well. What can Australia learn from Singapore?

GM: Well, another very interesting question you’re asking. It’s actually quite difficult to untangle the reasons for a country’s performance. And when we compare Singapore – which as you say performed at the top of the world in this 2022 cycle in reading, mathematical and scientific literacy, and has performed near the top of the world all along – it’s very hard to untangle the reasons for that, and it’s hard to compare what’s essentially a city state, Singapore, with a country the size of Australia. … and there are cultural differences as well, cultural differences perhaps that lead students to be more motivated to make more effort and so on.

But, having said that, there are some interesting differences between Singapore and Australia, I think. And one of those interesting differences is that Singapore makes a really big effort to recognise and address students’ different learning needs. One way they do that is, right from the beginning of school children who require more support with, say, English or mathematics are given extra support. They have specially trained teachers who provide additional support to children who may be slipping behind or struggling with their learning, right from that very early point. At the end of 4th grade, year 4, students then move into one of 2 levels. In areas, again, like English and mathematics, in core areas of learning, there’s a foundational level and there’s a standard level and the goal there is to teach at where students are up to in their learning, to recognise they’re at different points. At the end of primary school students are then streamed as they enter secondary school, they’re streamed into 3 different classes (or they have been, historically), and students in the top stream, of course, are taught the more demanding material, more demanding mathematics if it’s mathematics we’re talking about, students in the lower stream are taught the least demanding material. But again, the objective there is to recognise that students are at different points in their learning and are ready for different kinds of challenges and have different kinds of learning needs.

In Australia, we know that streaming is not a solution. Streaming ends up locking students into streams, it sets ceilings on how far some students can progress in their learning. It often labels students, so they become labelled with the stream that they end up in. Singapore understands this too. Singapore is in the process of moving away from separately streamed classes, and what it will do instead is have all students in the same class, but it will have 3 levels within the class at which students are working. So again, the attempt is being made there to recognise that students are at different points in their learning and have different learning needs. And I think, as I say, Singapore does a pretty good job of that and there may be a lesson there that we could learn in Australia.

We’ll be back with more from Professor Geoff Masters after this quick message from our sponsor.

You’re listening to a podcast from Teacher magazine, supported by MacKillop Seasons, whose Seasons for Life project supports young people affected by suicide and other loss events throughout Australia. Free for Australian high schools and based on the strong evidence-base of the Seasons for Growth change, loss and grief education programs, the Seasons for Life project builds wellbeing, resilience, social and emotional coping skills, and strengthens supportive relationships.

JE: So, can we talk about some of the other top performing countries then. Your new book that’s just come out Building a world-class learning system: Insights from top-performing school systems, you looked at 5 different countries there. There’s British Columbia, which is a province in Canada, there’s Korea, Finland, Estonia and…

GM: Hong Kong.

JE: Hong Kong, thank you. So, they’ve all undergone, what’s interesting about those countries, they’ve all undergone some sort of transformational change in education. What are some of the things that we can learn from that?

GM: I think there are many things we can probably learn from at least some of those jurisdictions that you mentioned. One of the things that I thought was interesting in my analysis was that they all seemed to understand the importance of addressing the framework, or the context within which schools work. I mean things like, the school curriculum, assessment and reporting requirements, credentials, how teachers are prepared and developed and so on. So, they recognise that need and they understand that to have an impact on teaching and learning, you need to transform that structure, that framework within which teachers and schools work. And they’re all really focused on the goals of better preparing young people for their futures and ensuring that every young person is learning successfully. And they’re using that strategy of reforming their curriculum and so on to do that.

And when it comes to the curriculum, for example, they believe as we do in Australia, that it will be important to move beyond curricula that are heavily content based. I mean, content continues to be important, facts and procedures are important, but it’s a question of getting the balance right. And so, what they are increasingly focusing on is what they often call ‘deeper learning’ – understanding of important concepts and principles in subjects, rather than memorising and reproducing lots and lots of detail. Giving students the opportunity to apply those understandings, those deeper understandings, to transfer their knowledge to new contexts, developing skills in applying knowledge, skills like thinking skills, critical thinking, creative thinking, problem solving, working with others, collaborating, communicating with others in that process.

So, they’re broadening their understanding of what it is we value in schools and what the curriculum should be promoting. They often refer to this as more holistic, you know, paying attention to the whole person, including things like dispositions and personal attributes, things like resilience and persistence and growth mindset, those sorts of things. So, that’s one way in which these jurisdictions and others are trying to reform and often they would say transform their learning system, the framework within which schools work, in an attempt to better prepare young people for their future.

They’re also working to achieve more flexible learning arrangements – and this is true of most of them – most of the 5 that you mentioned. They recognise that if every student is to have their needs met and to learn successfully, we need to move to more flexible arrangements. For example, if a student needs more time to master something, we need to find a way to give them more time, or if they’re ready to move on to something more advanced, more challenging, we need to find ways to allow them to do that. So, they’re looking at how they can introduce more flexibility.

I’ll give you an example. Finland is doing this by defining a phase of schooling that runs over 3 or 4 years; starts before school, so back, kindergarten somewhere, and it continues into the first couple of years of school. And what they’re doing is, instead of saying ‘this child is in grade 1, so we have to teach them the grade 1 curriculum’ they will recognise that across that 3- or 4-year range, there are going to be children at many different points in their learning. There’ll be some 7-year-olds who are still reading at the level of the average year 5 child, for example. And so, the intention of kind of moving away from, you know, very structured year levels into a broader phase of schooling, is to support teachers to identify where individuals are at in their learning and to do what they can to target their learning needs. Recognising the variability that exists within that range.

Other things that systems are doing are things like having the same teachers stay with the same class for multiple years – in some cases, almost all the way through primary school. And again, the reason for that is they believe that there are benefits in having a teacher get to know a child and the child’s long-term growth or progress. They believe that the teacher will be better able to target the child’s needs if they’ve been monitoring the progress they’re making over an extended period of time.

And then there are other systems that are trying much more radical approaches, not within this group of 5 jurisdictions so much but, you know, if you look at places like Wales. What Wales is doing is, it’s saying, ‘we really need to break out of this heavily time bound lockstep approach to learning’ and what they have done is to define a sequence of levels – [let’s] stick with mathematics for a minute – a sequence of levels in mathematics, with the intention that children will progress through those levels across multiple years of school. So, they’re not levels specific to a particular year of school, they’re levels that apply across multiple years of school. And children move from … the intention is that students will move from level 1 to level 2 to level 3. The point is that they are open to the possibility that students of the same age or in the same year of school could be at different levels in their mathematics, and they understand that the important thing is to try to target the levels that individual students are at.

So, these are some of the ways that attempts are being made to make the curriculum more flexible. And as I’ve been saying, in many countries, including Australia, the curriculum is pretty rigid and structured and heavily time bound. All students tend to be taught the same material at the same time for the same amount of time. They’re then assessed and graded on that body of content, and then they move in lockstep to the next body of content, where the whole process is repeated. And we know that the consequence of that kind of assembly line model of schooling is that some students fall behind and some students fall increasingly behind as the curriculum becomes increasingly beyond their reach. So yeah, the issue is people are thinking about flexibility and that has implications for assessment too, so assessments, not just the process of: How well have you learned this body of content that I’ve just taught? How much of it can you demonstrate? But, where are you in your long-term progress? What point have you reached? What do you know? What do you understand? What can you do and what does that mean for the next steps in learning? And how can I use that information to monitor your long-term progress as a learner?

JE: Yeah, there’s an awful lot going on internationally. And as you say in the book, actually all nations, not just the 5 that that you’ve looked at, all nations are grappling with kind of those same questions aren’t they about how we prepare students for life and how we get them to meet their potential at school as well. So that’s really interesting. The other point you were making about curriculum there, yeah, we don’t want a narrow curriculum but then again, we also don’t want, you know, the old ‘mile wide, inch deep’ version either we want that mastery learning. So, there’s a lot to think about there in terms of Singapore, which we spoke about earlier on, and those 5 systems that you’ve covered in your book. How does that impact on how we think about Australia then? Where do we go to from here, in Australia?

GM: Yeah, very good question. I mean what we can see in Australia, as I said, is that we have about half of students by 15 years of age according to these latest PISA results, about half of all students performing below the National Proficient Standard that we expect them to be at, at 15 years of age. So, the question is, why is that the case and what can we do about it? And there are various suggestions or theories here.

One suggestion is that maybe Australian students just don’t try; they’re not motivated when they sit PISA, whereas students in other countries are motivated and do try, and maybe Australian students could do better if they try. That may be true. It’s very hard to test that hypothesis. It may be true, but I would say if that’s the case, that may itself be a symptom of a problem. It may be a symptom of the problem that we’re not sufficiently engaging students in mathematics learning. We’re not helping them to understand the meaning and the relevance of mathematics as well as we could be.

Another suggestion that’s sometimes made is that the problem is teachers and teaching. That maybe they’re not using the right teaching methods. Maybe we need to find better teaching methods for them to use. And again, I’m sure that’s true of some teachers. We could improve the quality of the teaching for some I’m sure, but you know, when you look at what I was just saying in terms of the performance of Australian students, I find it hard to imagine that teachers are not capable of teaching things like fractions and percentages and decimals and reading a pie chart. So, I don’t, I’m not convinced that that’s the problem and I think it’s too easy to slip into blaming teachers for the problem.

A third suggestion that’s made is that maybe our curricula are not rigorous enough. Maybe we need to lift our standards, put more challenging content into our curriculum, add more stuff to the curriculum. And yes, that may be a possibility. But again, I don’t see how adding material to the curriculum, adding higher level content, will address this issue of the 50% of kids who are still not really mastering what they should have learned in primary school. You know, if you add more rigour to the secondary school curriculum it’s probably just going to mean they’ll struggle even more with that content. So, I’m not sure that any of those things is really the answer.

The reality is that we have these students who have fallen behind, probably fallen increasingly behind, as I said earlier, as the curriculum has become further and further out of their reach, as they’ve lacked the prerequisites for the curriculum that they’re about to be taught. And I think, personally, the answer lies in what I was talking about before, more flexibility in the curriculum. Not saying everybody has to move at the same time to the next curriculum, whether you’ve mastered the content or not, because we can see, graphically, in the picture that I showed, that that is leading many students to sink towards the bottom of the distribution. They fall further behind. What we need are strategies for identifying firstly and better understanding the points that individuals are at in their learning, and then good strategies to support teachers to address those needs.

Again, if you look internationally, you can see that some of these jurisdictions do an unusually good job of identifying and addressing the needs of students who are beginning to slip behind in their learning. They have teachers whose job is to do that, they have mechanisms of various kinds for identifying, diagnosing and addressing the needs of students so that they don’t have large percentages of students who are slipping behind.

So, I think they’re some of the challenges for us. We need to think radically. We can’t keep doing what we’re doing and expect things to improve. They’ve levelled out, yes, but long term there’s been a significant decline, so we need to change. We need to transform what we’re doing. We need to transform it in a way that is consistent with what we know about learning. And what we know about learning is that the way to maximise an individual’s likelihood of learning successfully is to meet them where they are, to address their current learning needs, to provide them with appropriate stretch challenges that are likely to lead to further growth or progress. And I think just to repeat what I’ve been saying, an issue for many of our students in Australia is that they’re being taught things that they’re not ready to learn and other students perhaps are being taught things they already know. And they’re the challenges that we need to address.

JE: Yes, absolutely. So, as I said, there’s an awful lot to digest there from the results. As always, then, I’d encourage listeners to take a look at the full reports that have been released in Australia – there’s a PISA in Brief and a Volume I – and then there’s an international PISA set of reports as well. I’ll put links to all of those in the transcript of this podcast. Again, you can just head over to teachermagazine.com

to find that. For now, though, Professor Geoff Masters, thanks very much for sharing your expertise with Teacher.

GM: You’re very welcome.

That’s all for this episode, but we’ll be speaking more with Professor Geoff Masters in the new year for a 3-part miniseries exploring how 5 of the top-performing jurisdictions in PISA in recent years – British Columbia, Estonia, Finland, Korea and Hong Kong – are transforming their education systems. Stay tuned for that one. If you want to keep listening now, you can access 300 episodes in the Teacher archives over at teachermagazine.com or wherever you get your podcasts. Before you go though, please leave a review on the podcast channel; it helps people like you to find the podcast and it’s also a great support for team, so thanks for that.

You’ve been listening to a podcast from Teacher, supported by MacKillop Seasons, Seasons for Life, supporting schools and young people affected by suicide and other significant losses. Visit mackillopseasons.org.au.

References and related reading

De Bortoli, L., Underwood, C., & Thomson, S. (2023a). PISA 2022. Reporting Australia’s results. Volume I: Student performance and equity in education. Australian Council for Educational Research. https://doi.org/10.37517/978-1-74286-725-0.

De Bortoli, L., Underwood, C., & Thomson, S. (2023b). PISA in Brief 2022: Student performance and equity in education. Australian Council for Educational Research. https://doi.org/10.37517/978-1-74286-727-4.

OECD. (2023a). PISA 2022 Results (Volume I) The State of Learning and Equity in Education. OECD.

OECD. (2023b). PISA 2022 Results (Volume II) Learning During – and From – Disruption. OECD.

Masters, G. N. (2023). Building a world-class learning system: Insights from some top-performing school systems. National Center on Education and the Economy. https://research.acer.edu.au/tll_misc/43

[ad_2]

Source link